Chapter 9

Types of Data Checks

By Ian Tebbutt

In the last chapter, we looked at data cleaning and the checking processes that are necessary to make that happen. Here, we’ll take a more in-depth look at data checking and talk about other validation processes, both before and after cleaning occurs.

Data checking is crucial if you and your audience are going to have confidence in its insights. The basic approach is quite straightforward: you have fields of data and each of those fields will have expected values. For instance, an age should be between 0 and 120 years (and in many cases will be less than 80 years). Transaction dates should be in the recent past, often within the last year or two, especially if you’re dealing with an internet-only data source, such as a Twitter stream.

However, data checking, although easy to understand and important to do, is a complex problem to solve because there are many ways data can be wrong or in a different format than we expect.

When to Check

Consider this dataset from a telecom company with information about customers who are changing phone numbers. Here, they provided the database but didn’t check the data which were aggregated from hundreds of smaller phone service providers. The database is still in daily use and is a great example of why checking is important. Imagine you’re tracking the types of phone charges by age. The example below shows a few of the issues.

- PhoneNumberType mixes codes and text

- Age field has 0 meaning unknown—not good for averages, and is 112 a genuine age?

| RecordId | PhoneNumberType | Age | New Customer | Price |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | MOBILE | 0 | NO | $12.45 |

| 2 | Mobile | 47 | Y | 12 45 |

| 3 | Land Line | 34 | YES | 37 |

| 4 | LandLine | 23 | YES | 1.00 |

| 5 | LL | 112 | Y | $1K |

The basic rule for data checking is check early, check often. By checking early, when data are first entered, there is a chance to immediately correct those data. For example, if your "New Customer" field expects the values YES or NO, but the user enters something different, such as an A or a space, then the user can be prompted to correct the data. If the validation isn’t done until later then incorrect values will reach the database; you’ll know they’re wrong but will be unable to fix the issue without returning to the user to ask for the information. Occasionally, it’s possible to compare incorrect fields with other linked datasets and then use that information to fix the original data. That can be complex and lead to further issues, since you have to decide which data source is correct.

If you’re in the happy position of controlling how the data are gathered, you have a great advantage, as one of the easiest forms of checking is done as soon as the data are entered. This type of data check is called a front-end check or a client-side check because it happens at the moment that the user enters the data, before the data are submitted to the database. This is most commonly done by making sure that your data collection application or web page is designed to only accept valid types of input. You have probably encountered this type of data validation yourself when filling out forms on the web before.

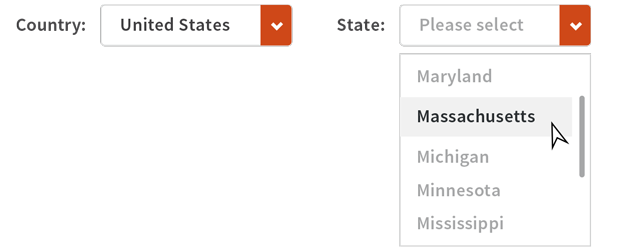

For example, states and countries should be selected from a list and if you’re dealing with international data, the choice of country should limit which state choices are available.

In this way your system will be constrained to only allow good data as they are entered. The approach isn’t perfect though. A classic internet speed bump is data entry that waits until submission before letting on there was an issue in a field at the beginning of the form. A better approach is to check every field as it is entered, but that has other disadvantages as it can be harder to code and can result in a continual stream of checking requests being sent to the server and potential error messages being returned to the user. As a compromise, some simple checking and validation can be carried out entirely in the browser while leaving the more complicated work for server-side processing. This will be necessary as some checking will require data or processes that are only available on the server itself. This often occurs when secure values—credit card verification, for instance—are being checked.

Other good survey design policies to consider to minimize data preparation time include:

- Decide how you want names to be input in advance. Is it okay for people to add things like Jr, DVM, PhD, CPA after their names or do you want these to be stored separately from the name itself? If so, do you want professional designations to be in a different field than suffixes like Jr, II, III? Do you want first and last names to be separate fields?

- Set up forms so that phone numbers and dates can only be input the way you want them to be stored (more about dates below). Determine if you want to collect office extensions for office phone numbers. If so, set up a separate extension field.

Trust Nobody

No matter how well you have designed your form and how much validation you have put into your front-end checks, an important rule of thumb is never trust user data. If it has been entered by a person, then somewhere along the line there will be mistakes. Even if there are client side checks, there should always be server side or back-end checks, too—these are the checks that happen after the data are submitted. There are many good reasons for this. You might not have designed the data gathering tools and if not, you could have different front end applications providing data. While some may have excellent client side checks, others might not. Unclean or unchecked data may arrive in your system through integration with other data services or applications. The example telecom database had too many owners with little oversight between them, resulting in a messy dataset. A small amount of extra effort up front saves us time and frustration down the road by giving us a cleaner dataset.

A second golden rule is to only use text fields where necessary. For instance, in some countries it’s normal to gather address data as multiple fields, such as Line1, Line2, City, State, Country, postcode, but in the UK it’s very common to just ask for the postcode and the street number as those two pieces of information can be then be used to find the exact address. In this way the postcode is validated automatically and the address data are clean since they aren’t not entered by the user. In other countries, we have to use text fields, and in that case lots of checking should occur.

Commas in data can cause all kinds of problems as many data files are in comma separated (CSV) format. An extra comma creates an extra unexpected field and any subsequent fields will be moved to the right. For this reason alone it’s good to not cut/paste data from an application; instead save to a file and then read into your next application.

| Title | Name | FamilyName | Address1 | Address2 | Town | State | Country | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bill | Short | 13 | A The Street | Hastings | VIC | AUS | ||

| Mr | William | Tall | 27 The Close | Guildford | VIC | AUS |

An additional comma in the second record has pushed the data to the right. This is an easy problem for a human to spot, but will upset most automated systems. A good check is to look for extra data beyond where the last field (“country”) would be. This example emphasizes the importance of combining computerized and manual approaches to data checking. Sometimes a quick visual scan of your data can make all the difference!

Data Formats and Checking

When dealing with numbers there are many issues you should check for. Do the numbers make sense? If you’re handling monetary figures, is the price really $1,000,000 or has someone entered an incorrect value? Similarly, if the price is zero or negative, does that mean the product was given away or was someone paid to remove it? For accounting reasons many data sources are required to record negative prices in order to properly balance the books.

In addition, checking numeric values for spaces and letters is useful, but currency and negative values can make that hard as your data may look as follows. All of these are different and valid ways of showing a currency, and contain non-numeric character values.

$-1,123.45

(1123.45)

-US$1123.45

-112345E-02

Letters in numbers aren’t necessarily wrong, and negative values can be formatted in a variety of ways.

Dates also exhibit many issues that we have to check for. The first is the problem of differences in international formatting. If you see the date 1/12/2013, that’s January 12, 2013 in America, but in the UK it’s December 1. If you’re lucky, you’ll receive dates in an international format such as 2014-01-12. As a bonus, dates in this standardized format (http://whatis.techtarget.com/definition/ISO-date-format) can be sorted even if they’re stored as text. However, you might not be lucky, so it’s important to check and make sure you know what dates your dates are really supposed to be, particularly if you’re receiving data from respondents in multiple countries with different date formats. A good way to handle this if you are designing the data entry form is to make the date field a calendar button field, where the user selects the date off a calendar instead of entering it manually. Alternatively, you can specify the format next to the entry box as a sort of instruction for the user.

Another checking task that you may encounter is the analysis and validation of others’ work to make sure the visualizations and numbers actually make sense. This can happen in a work situation where you need to proof other people’s work of others or online where public visualizations will sometimes provide the underlying data so you can try your own analysis. In both instances the first check is to just recalculate any totals. After that, look at the visualization with a critical eye: do the figures make sense, do they support the story or contradict it? Checking doesn’t have to be just for errors. It can be for understanding, too. This will give you good experience when moving on to your own data checking and is the first thing to try when someone passes you a report.

Data Versions

Another big source of data checking problems is the version of the data you’re dealing with.

As applications and systems change over the years, fields will be added, removed, and—most problematic—their purpose will be changed. For instance the Australian postcode is 4 digit and is stored in a 4 character field. Other systems have been changed to use a more accurate 5 digit identifier called the SLA. When data from those systems are combined, we often see the 5 digit values chopped down to fit into a postcode field. Checking fields for these kinds of changes can be hard: for postcodes and SLAs, the lookup tables are in the public domain, but it takes additional investigation to realize why a location field with 4 digits matches values from neither table.

You should consider collecting additional fields which won’t be part of the actual visualization or final report but will give you important info about your records, like when they were created. If new fields are added after the dataset is created, any existing records won’t have that field filled and if someone is improperly handling the dataset, the older records may have new numeric fields filled with zeroes. This will throw off averages and the effect on your visualizations would be huge. If you have the record creation date, you can go through and change the incorrectly added zeroes to a missing value to save your data. For those fields that have been removed, a similar issue might be seen. It’s relatively rare for unused fields to be removed from data but they can sometimes be repurposed, so figuring out the meaning of a specific piece of data can be challenging if the functional use of a field has changed over time.

| Amount | PaymentType | ServerId | CreatedOn |

|---|---|---|---|

| $100 | CC | ||

| $143 | Cash | ||

| $27 | Amex | 237 | 3/1/2013 |

| $45 | Cash | 467 | 3/1/2013 |

Here you can see the effect of adding two new fields, ServerId and CreatedOn, to an existing data source. It’s likely that change was put into place 03/01/2013 (March 1, 2013), so if your analysis is only looking at data since that date then you can track sales/server. However, there’s no data before that in this source, so if you want to look at what was happening on January 1, 2013, you need to find additional data elsewhere.

One of the most important checking issues is that the meaning of fields and the values in them may change over time. In a perfect world, every change would be well-documented so you would know exactly what the data means. The reality is that these changes are rarely fully documented. The next best way of knowing what the data in a field really represents is to talk the administrators and users of the system.

These are just some of the steps that you can take to make sure you understand your data and that you’re aware of potential errors. In the next chapter, we’ll talk about some of the other sneaky errors that may be lurking in your data, and how to make sense of those potential errors.