Chapter 4

Types of Survey Questions

By Ginette Law

After you’ve decided what type of survey you’re going to use, you need to figure out what kinds of questions to include. The type of question determines what level of data can be collected, which in turn affects what you can do with the data later on. For example, if you ask about age and you record it as a number (e.g., 21, 34, 42), you’ll have numeric data that you can perform mathematical operations on. If you instead ask for a person’s age group (e.g., 18-24, 25-34, 35-44), you’ll have ordered categorical data: you’ll be able to count how many people were in each group, but you won’t be able to find the mean age of your respondents. Before you create your survey, it’s important to consider how you want to analyze your final results so you can pick question types that will give you the right kind of data for those analyses.

Open vs. Closed Questions

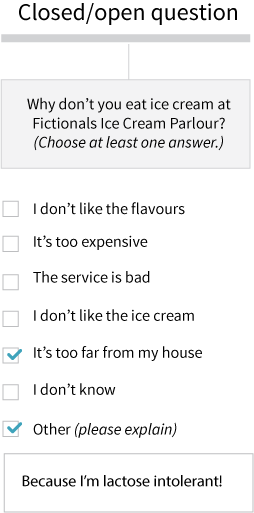

Open (or open-ended) questions are used when you want to collect long-form qualitative data. You ask the person a question without offering any specific answers from which to choose. This is often a good option to discover new ideas you may have overlooked or did not know existed. In a closed question, however, a limited number of specific responses are offered to answer the question. Closed questions are used when you already have an idea what categories your answers will fall into or you’re only interested in the frequency of particular answers.

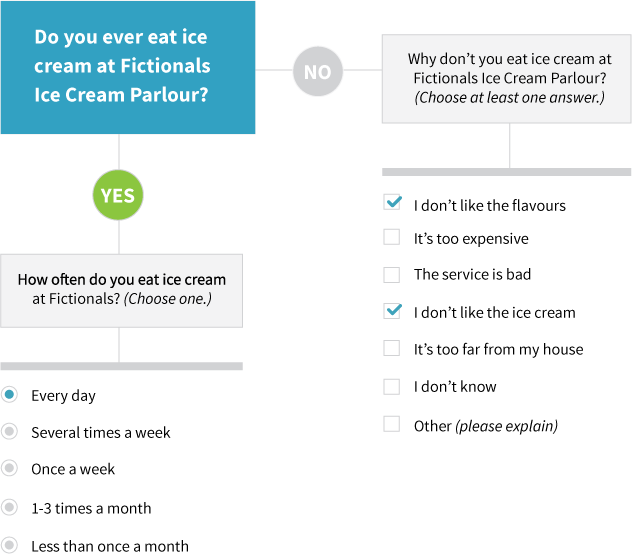

Let’s pretend you work for an ice cream parlour called Fictionals. You want to know why some people don’t come to your store. Here are open and closed questions you could ask to find out their reasons.

In the closed question, you offer the most probable reasons why people would not go eat ice cream at your store, whereas in the open question, you just ask why they don’t eat at Fictionals and allow respondents to answer however they want.

When you ask an open-ended question you gain new insight to why some people might not try your ice cream: it’s not because they don’t like ice cream or they don’t like Fictionals, it’s because they can’t eat it! With this new insight, you could choose to offer a new type of ice cream and attract a clientele you didn’t appeal to before.

This is a distinct advantage of open-ended questions, and it’s particularly useful if you’re doing exploratory research and will primarily be reading through the responses to get a sense of how people responded. However, it takes considerably more work to analyze and summarize these data.

When you think that most people will give more or less the same answer, you can combine an open and closed question to get the best results. This is usually done by offering a number of predefined choices, but leaving room for participants to explain their response if it falls under the “Other” category. Here is how the same question would look if you transformed it into a combined open and closed question:

Closed Question Types

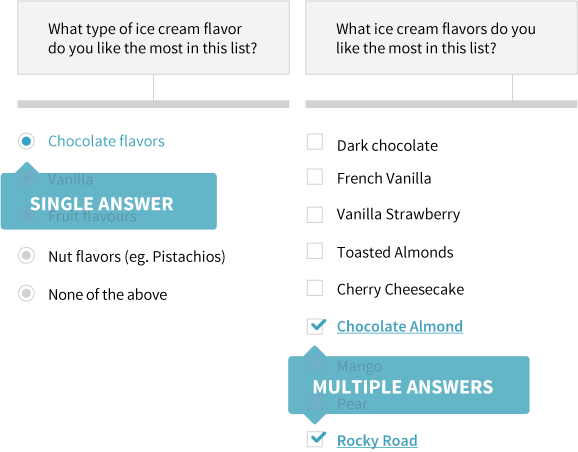

Multiple Choice Questions

Sometimes you’ll want the respondent to select only one of several answers. If your survey is online, you use radio buttons (or circles), which indicate to choose just one item. If you want to allow the respondent to choose more than one option, you should use a checkbox instead. Here is what it looks like in practice:

If your survey is a paper or administered survey, you would use printed or verbal directions to indicate how many options the respondent should pick (e.g., “Please choose one”; “Please select up to 3”; “Please select all that apply”).

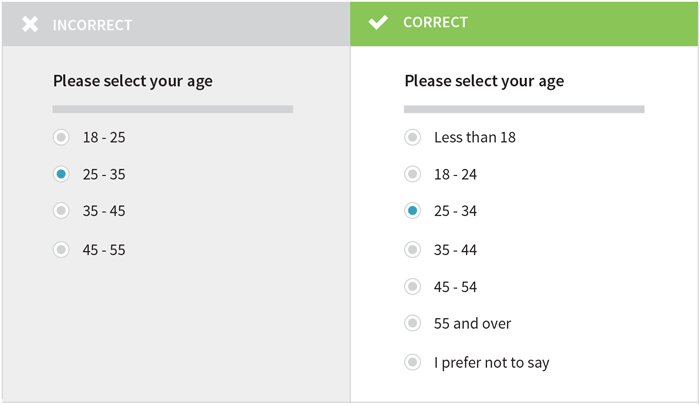

Answer choices should not overlap and should cover all possible options. This is called having “mutually exclusive and exhaustive” categories and is crucial for sound survey design. Consider the situation below:

In the left set of choices, someone who is 25 wouldn’t know whether to select the 18-25 button or the 25-35 button, and someone who is 60 wouldn’t have any option to select at all! The set of age categories on the right is better because it includes all possible age groups, the age choices don’t overlap, and it allows people the choice to withhold that information if they choose to.

It is advisable to include a “Prefer not to answer” option for questions that may be of a personal nature, such as race, ethnicity, income, political affiliation, etc. Without this option, people may skip the question altogether, but you won't be able to tell later on who skipped the question on purpose and who missed it accidentally, which can be an important difference when you analyze your data.

It won’t always be practical to list every possible option. In that case, including “None of the above” or “Other” choices may be helpful. This makes it less likely that people will just skip the question and leave you with missing data. You may also consider including a “Not Applicable” (i.e., “N/A”) choice for questions that may not apply to all of your respondents, or a “Don’t know” choice for questions where a respondent may not not have the information available.

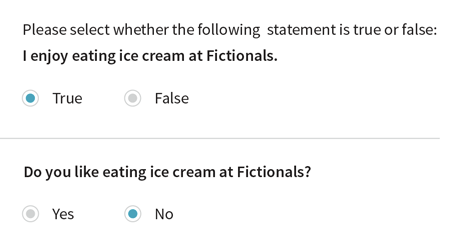

Dichotomous Questions

Dichotomous questions are a specific type of multiple choice question used when there are only two possible answers to a question. Here are some classic examples of dichotomous type questions:

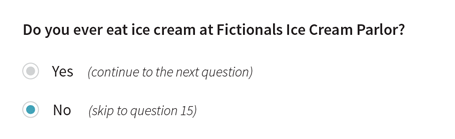

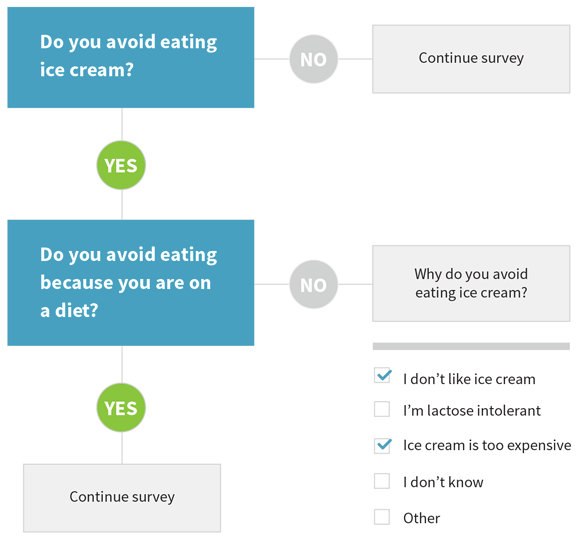

You can use dichotomous questions to determine if a respondent is suited to respond to the next question. This is called a filter or contingency question. Filters can quickly become complex, so try not to use more than two or three filter questions in a row. Here’s an example of the logic behind a filter question:

In an online survey or administered survey, answering “Yes” to the question “Do you ever eat ice cream at Fictionals Ice Cream Parlour?” would take a respondent to the question about how often they do, while selecting “No” would open the checkbox response question asking why they don’t eat there. In a paper survey, all questions would need to be listed on the page and couldn’t be presented conditionally based on a specific response. You could use a flowchart form like in the diagram above, or you could employ skip directions, as illustrated below.

Scaled Questions

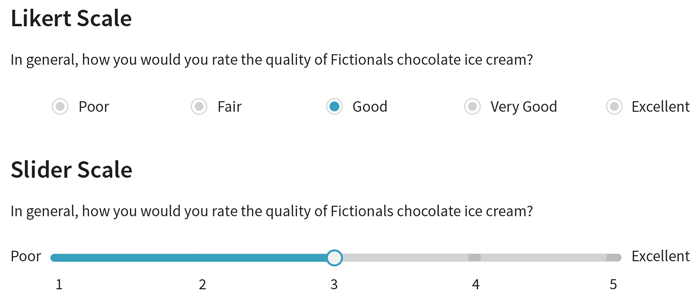

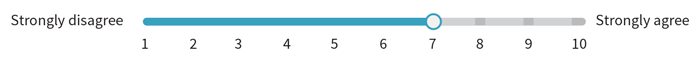

Scaled questions are used to measure people’s attitudes, opinions, lifestyles and environments. There are many different types but the most commonly used are Likert and slider scales. The main difference between the two is that a Likert scale consists of ordered categories whereas a slider scale allows respondents to make a mark indicating their response anywhere along a scale. As a result, a Likert scale-type question will give you data that are measured at an ordinal level while a slider scale will give you data that are measured at an interval level.

In the example above, the same question is asked twice, once with a Likert scale and once with a sliding scale. Notice that in the Likert scale there are five categories. Scales with an odd number of categories allow participants to agree, disagree, or indicate their neutrality; scales with an even number of categories only allow participants to agree or disagree. If you want to allow for neutrality, scales with an odd number of categories are usually preferred; however, you should use an even number if you want to require the respondent to choose one direction or the other. This is called a “forced question.”

Likert Scale

Likert scales are usually limited to a five-category scale, as it is often difficult to clearly display a larger number of categories. The most common Likert scales you will find are:

- Opinions and attitudes: “How much do you agree with…?”

Possible answers: strongly agree, agree, neither agree or disagree, disagree, strongly disagree - Frequency: “How often do you…?”

Possible answers: always, often, sometimes, rarely, never - Quality: “In general, how do you rate the quality of…?”

Possible answers: excellent, very good, good, fair, poor - Importance: “How important would you say {topic} is…”

Possible answers: very important, important, somewhat important, not at all important

Slider Scale

Slider scales are useful when you want to have a more precise reading of a respondent’s views. These scales are most easily implemented in an online survey, since the computer will calculate the position of the marker; when used on a paper survey, you will need to have someone measure the marker’s location on the scale manually. Slider scales may be more practical than Likert scales when conducting a survey that is being translated into multiple languages since text categories are not always easy to translate.

When creating a scale, whether Likert or slider, never forget to label the first and last points in your scale. Otherwise, your respondents may misinterpret your scale and give you inaccurate or misleading data.

Question Wording

It’s extremely important to think about how you word your questions when developing a survey. Here are a few key things to keep in mind:

Focus

Each question should be specific and have a defined focus.

How many times have you eaten ice cream in the last month?

This question focuses on one issue (frequency of ice cream eating) and is specific (a certain time period).

Do you avoid eating ice cream because you are on a diet? [Answer: Yes, I avoid ice cream, but not because I am on a diet]

This question is poorly worded for a few reasons: it is both leading and too specific. It assumes that the respondent is in fact on a diet and that this is why he or she doesn’t eat ice cream. A better wording would be “Why do you avoid eating ice cream?” with “I’m dieting” as one of a number of options that the participant can choose from.

You should also avoid using the word “and” if it is connecting two different ideas within a single question. Remember, each question should focus on only one issue at a time: otherwise, you won’t be collecting the best data that you can. By compounding multiple thoughts into a single question, you reduce the accuracy of participants’ responses and thereby limit the claims that you can make from those data. Instead, consider using filter questions to obtain the desired information. For example:

Precision

Not everyone will interpret all words and phrasings in the same way, even if the meaning seems obvious to you. To reduce the chance of participants misinterpreting your question, you can parenthetically define ambiguous terms or give additional context as appropriate. Try also to avoid confusing wordings, such as those that use double negatives or many subordinate clauses. Be careful to also not use words that are loaded or have many highly-emotional connotations.

| Do | Don’t |

|---|---|

|

|

Brevity

Your questions should be relatively short, except where additional wording is absolutely necessary to provide context or to clarify terminology. Long, complex questions can quickly become confusing to participants and increase the chances that they will respond without fully understanding what is being asked, or worse, skip the question entirely! If your question seems to be getting too long, consider whether there is any unnecessary information that you can take out or if you can split it up into several smaller questions. Alternately, you may want to have a short paragraph of explanatory text that is separate from the question itself: that way participants will have all necessary background information, but can also easily pick out and digest what is actually being asked.

| Do | Don’t |

|---|---|

| Please list your three favorite ice creams in order of preference. | Can you please tell us what ice cream flavors you like and what are your first, second, and third favorites? |

Biased and Leading Questions

Biased or leading questions can easily skew your answers if you do not pay close attention to your wordings. Avoid over-emphasizing your statements and keep an eye out for questions that create “social desirability effects” where respondents may be more likely to answer according to what society views as proper or socially or morally acceptable.

| Do | Don’t |

|---|---|

| Do you agree that ice cream vendors in our city should offer peanut-free products? | Do you agree that ice cream vendors that serve peanuts are a severe hazard for the well-being of our children? |

Notice how the second question tries to bias the respondent by using strong or affective phrases such as “severe hazard.” You should try to keep your questions as value-free as you can: if the question itself suggests how the participant is expected to answer, it should be reworded.

A Few Final Things…

There are few final things to consider when developing your survey questions:

- If possible, consider varying the type of questions you use to keep your respondents engaged throughout the survey. You have a variety of question types to choose from, so mix it up where you can! (But do keep in mind that each type of question has a specific purpose and gives you more or less specific data.)

- Think about how certain words can have different interpretations and remember that meanings are often embedded in culture and language. Be sensitive to different cultures if you are examining several groups within a population.

Designing Your Questionnaire

Once you have identified the purpose of your survey and chosen which type you will use, the next step is to design the questionnaire itself. In this section, we’ll look at the structure, layout and ordering of questions. We’ll also talk about some key things to keep in mind once you’re done.

Questionnaire Structure

Do you remember when you were taught in grade school that every essay should have an introduction, body and conclusion? Questionnaires should also have a certain structure. The major parts of a questionnaire include the introduction, main topic, transitions between topics, demographic questions, and conclusion.

Introduction

Always start your survey with a brief introduction which explains:

- the purpose of the survey;

- who is conducting it;

- the voluntary nature of the participant’s involvement;

- the respect for confidentiality; and

- the time required to complete the survey.

Main Topics

Generally, it is best to start with general questions and then move on to more specific questions.

- Ask about objective facts before asking more subjective questions.

- Order questions from the most familiar to least.

- Make sure that the answer to one question does not impact how the participant interprets the following question.

Transitions Between Topics

Use transitions between groups of questions to explain a new topic or format. For example: “The next few questions are related to the frequency of your TV viewing habits. Please choose the answer that best describes your situation.”

Demographic Questions

Unless you are using demographic questions as filtering criteria for survey eligibility, it is usually better to put them near the end of a survey. Typical demographic questions include:

- gender;

- age;

- income;

- nationality or geographic location;

- education; and

- race or ethnicity.

Conclusion

Thank the participants for their contribution and explain how it has been valuable to the project. Reiterate that their identities will be kept confidential and that results will be anonymized. If you wish, you can also include your contact information in case they have any additional questions related to the survey and also ask for their contact information if you are offering an incentive for completing the survey.

If you contact respondents in advance to invite them to participate in the survey, you should also explain why they have been selected to participate, when the survey will take place, and how they can access it.

General Layout

There are a few good rules to follow when designing the layout of your survey:

- Put your introduction and conclusion on separate pages from your questions.

- The format should be easy to follow and understand.

- Check that filter questions work as intended.

- Stick to questions that meet your goals rather than just asking every question you can think of. In general, survey completion rates tend to diminish as surveys become longer.

- Leave enough space for respondents to answer open-ended questions.

- Make sure to include all likely answers for closed-ended questions, including an “Other” option in case respondents feel that none of the provided answers suits them. Where appropriate, also include “Not Applicable” and “Choose not to respond” options.

- Ensure that questions flow well and follow a logical progression. Begin the survey with more general questions and then follow with more specific or harder issues. Finish with general demographic topics (e.g., age, gender, etc.), unless you are using these to screen for eligibility at the beginning of the survey. Group questions by theme or topic.

Some Further Considerations

Consider Your Audience

Think about the people who will be participating in your survey. Let’s say, for example, that you want to conduct a survey in a school where many students have recently immigrated to the country as refugees with their families and don’t yet speak the local language well.

In what language(s) should you conduct the survey? Should you only conduct the survey in the local language or instead prepare it in several languages? If you’re preparing different versions of the survey, who will ensure consistency among the translations?

What kind of vocabulary should you use? These are students who may not be taking the questionnaire in their native language. You will probably want to use fairly basic language, especially if many are not native speakers. We have not specified their age, but it would be useful to take this information into consideration when thinking about vocabulary.

Word Instructions and Questions Clearly and Specifically

It is important that your instructions and questions are simple and coherent. You want to make sure that everyone understands and interprets the survey in the same way. For example, consider the difference between the following two questions.

- When did you first notice symptoms? ______________________

- When did you first notice symptoms (e.g., MM/YYYY)? __ __ / __ __ __ __

If you want the question to be open to interpretation so that people can give answers like, “after I came back from my last trip,” then the first option is okay. However, if you’re really wondering how long each person has been experiencing symptoms, the second version of the question lets the respondent know that you’re interested in the specific time at which the symptoms first occurred.

Pay Attention to Length

We often want to collect as much information as possible when conducting a survey. However, extremely long surveys quickly become tedious to answer. Participants get tired or bored which in turn decreases the completion rate. After a while, you risk getting inaccurate responses from people who are trying to finish the survey as rapidly as possible. When reviewing your questionnaire, ask yourself, “Do I really need this question? Will it bring any valuable data that can contribute to my reason for doing this survey?”

Track Progress

It is good to indicate the respondents’ progress as they advance through the survey. It gives them an idea of their progression and encourages them to continue on. In a self-administered survey, a progress bar such as the one below could be placed at the beginning of each new section or transition.

In an administered survey, the interviewer can simply make statements such as:

- “We are halfway done.”

- “There are only two more sections left.”

- “Only a few more questions to answer.”

Train Interviewers

If you are conducting an administered survey, you will have to prepare your interviewers ahead of time, explain their tasks, and make sure that they understand all of the questions properly. You may also want them to be supervised when they are first conducting the survey to monitor for quality to control for interviewer effects.

Pretest

Pretesting means testing your survey with a few initial respondents before officially going out in the field. This allows you to get feedback to improve issues you might have with length, technical problems, or question ordering and wording. Sometimes this step gets skipped if there’s a tight deadline to meet, but you shouldn’t underestimate its value. It can save a lot of time and money in the end.

Anonymize Responses

We briefly mentioned response anonymization earlier when we talked about questionnaire structure. Sometimes, people are afraid to give an honest response for fear that it might be traced back to them. By anonymizing responses you will get more accurate data while protecting the identity of your participants. There are times when you may need to keep respondents’ contact information associated with their responses, like if you’ll be conducting a follow-up survey and will need to know what their initial answers were. Be clear in your survey about whether you’re anonymizing responses or not so respondents know if you’re storing their contact information.

You should always anonymize any results you present, whether the data you collect are anonymous or not.

Incentives

The use of incentives can be contentious. You want to encourage as many people as possible to participate in your survey, but you also don’t want people completing the survey just to get a reward. Larger reward amounts can also raise ethical concerns of participant coercion (i.e., having individuals participate when they would otherwise refuse due to personal discomfort, risk of repercussions, etc.).

If the survey is long and time consuming, consider giving a small reward or stipend if a respondent completes the questionnaire. If the survey is shorter, consider doing a prize drawing from respondents who complete the survey and choose to provide their contact information.

Wrapping Things Up

As you have noticed, there are a number of factors you will need to consider when you’re designing your survey and deciding what types of question to use. Survey creation can seem daunting at first, but remember this is the foundation of your data analysis. Getting this step right will make the rest of your work much easier later on.

For further reading, please see our resources section.